The Evolutionary Origins of Clothing

Listen to this article

Produced by ElevenLabs and NOA, News Over Audio, using AI narration.

The naked human is a vulnerable creature. Lacking the fur of our mammalian ancestors and relatives, we have bare skin that offers little defense against the sun’s brutal rays or wind’s biting chill. So instead, we have had to invent a technology to replace our long-lost fur: “portable thermal protection,” as the archaeologist Ian Gilligan calls it or, more simply, clothing.

Without clothing, humans would never have reached all seven continents. This technological breakthrough allowed our ancestors to live in Siberia during the height of the Ice Age, and to cross the frigid Bering Sea to the Americas some 20,000 years ago. But no clothing survives from this period. Not a single article of clothing much older than 5,000 years has ever been found, in fact. The hides and sinews and plant fibers worn by our ancestors all rotted away, leaving little physical trace in the archaeological record. Humans had to have worn clothing more than 5,000 years ago, of course. Of course! And in clever, indirect ways, experts have pieced together a surprising number of clues to how much longer ago.

For example, with lice. Head lice, which prefer to live in our hair, and body lice, which prefer to live in our clothing, are two distinct populations whose paths rarely cross. Head lice spread from head to head, body lice from body to body, but neither usually spreads from one to the other. In 2011, geneticists took advantage of this distinction to examine the origins of clothing in Homo sapiens. The advent of clothing, they posited, allowed some of the parasites that live in our hair to expand to a new niche on our body. Modern head lice and body lice diverged some 83,000 to 170,000 years ago, based on differences in their DNA. The invention of clothing by modern humans, according to lice DNA at least, could have occurred no later than those dates.

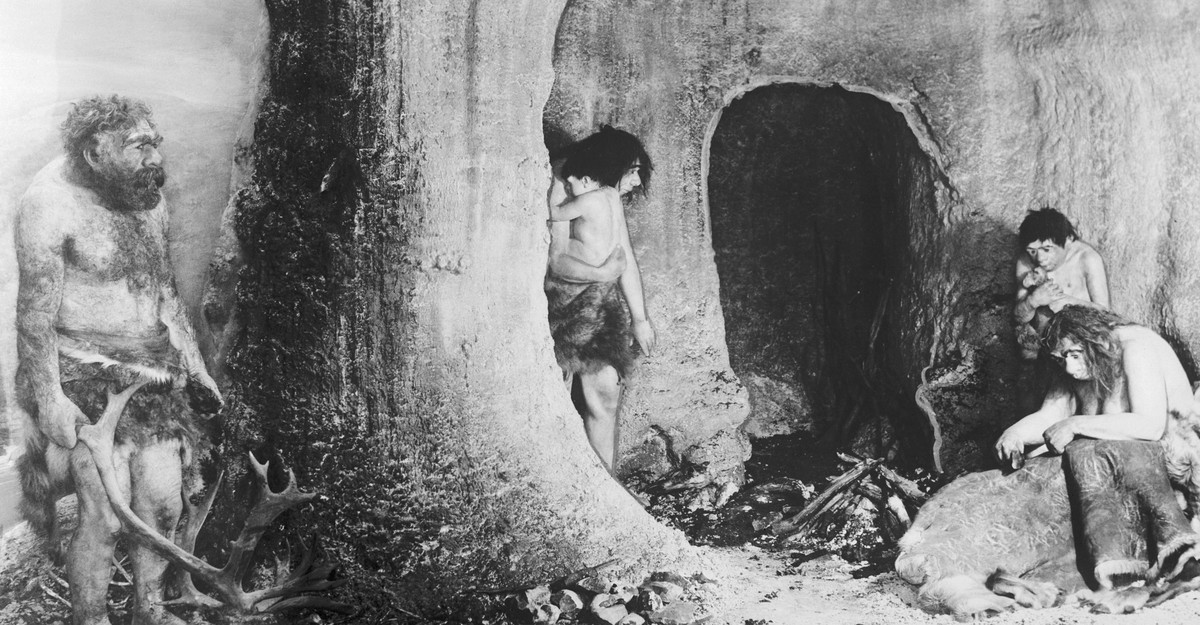

But Homo sapiens were not the first to invent clothing. Archaic humans who have since gone extinct probably wore clothes too. In cave sites as old as 800,000 years in China and in Spain, archaeologists have found stone tools resembling hide scrapers that could have been used by Homo erectus and Homo antecessor, respectively, to soften and prepare animal skins for clothing. About 300,000 years ago, another archaic human species left behind similar scrapers in what is now Germany, along with bear bones featuring cut marks that suggested the animals might have been skinned for their fur.

Neanderthals, who lived in Europe hundreds of thousands of years before Homo sapiens arrived, also likely made clothing to survive the cold winter. Archaeologists have found polished fragments of deer ribs resembling modern hide-working tools called lissoirs, which are used to burnish leather. Using a modern bone to smooth dry hide, experts were able to re-create the same microscopic patterns of tool wear. “The lissoirs are good evidence for working of leather,” Shannon McPherron, an archaeologist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology who studied the Neanderthal tools, told me in an email—but no one can prove how Neanderthals actually used them, beyond the analogy with contemporary leather tools. And indeed, interpreting any of the ancient-tool evidence is challenging for this reason: We can demonstrate how they might have been used for clothing, but we cannot prove how they were used.

Absent physical evidence of early clothing, archaeologists have also approached its origins in a different way, by asking when humans started needing clothing.

Early humans probably first lost their fur in the arid environment of Africa, where heat—not cold—was the most pressing concern. Moving in the heat only generated more heat, which we counteracted with sweating. The evaporation of moisture off our skin cools the underlying blood, a strategy that works so well that humans evolved into prodigious sweaters. “We have 10 times as many sweat glands per area as a chimpanzee,” says Daniel Lieberman, a paleoanthropologist at Harvard. “And we lost our fur.” The hair on our body became fine and short, unable to trap much heat or moisture. Our bare skin really is a key part of sweating: In a classic 1950s study, scientists found that shaved camels readily sweat 60 percent more than unshorn ones.

But this adaptation that served early humans so well in the heat became a maladaptation in Europe during the Ice Age, which ended only about 10,000 years ago. Even Neanderthals, who were likely better adapted to the cold with their broader chests and shorter limbs, could not have survived naked. According to one modeling study, Neanderthals would have needed to cover up to 80 percent of their body. Yet they seem to have made do with just simple clothing, such as animal skins turned into shawls or loincloths, says Gilligan, an honorary associate at the University of Sydney who examines the origin of clothing.

Gilligan draws a key distinction between simple, draped clothing and complex, fitted clothing, such as pants and shirts with enclosed legs and arms. Simple clothing is a primitive form of portable thermal protection. “But it’s not very good, for example, with windchill,” he told me. Fitted clothing is warmer but more difficult to make, requiring new tools such as awls or eyed needles. These sewing tools have never been found in Neanderthal sites. But Homo sapiens did make the leap to fitted clothing. The oldest eyed needles likely used by Homo sapiens were unearthed from sites 40,000 years or older in Russia; they’ve also been found in China dating back some 30,000 years.

As the Ice Age receded some 10,000 years ago, the thermal function of clothing became less paramount. Animal furs and skins, in fact, would have been too hot in the newly warm and humid interglacial summers. But clothing had by then taken on a social significance, Gilligan said, and humans in need of cooler clothing turned to lighter material made of woven fibers—a.k.a. cloth. He argues that this demand for clothing fibers ultimately helped push humanity toward agriculture. This argument is provocative though unproved, but climate and clothing are indeed intimately linked in their long history. For his part, Gilligan told me, he doesn’t really care about the modern stuff: “I dread having to shop for clothes. I tend to wear them until they fall apart.” What interests him is how clothing seems uniquely human, and how it sets us apart from even our closest animal relatives.